Our Work

- Home

- Our Work

Work Security

Rural households in need of work love MGNREGA. Many others who are not dependent on it hate it: farmers blame it for increasing local rates and for making labour availability already stressed by urban migration, even more scarce. Conservatives dislike the populism that this implies without making a distinction between the subsidies and write-offs that every sector in the economy enjoys. People bemoan the corruption that it has not helped curb.

Yet it’s the only social welfare benefit that is an entitlement.

And it’s the only financial tap at the Gram Panchayat level that is demand driven: people demand work, the Gram Panchayat approves this, the government provides the funds for this, and Hey! Presto! People get work.

Think of MGNREGA as an overdraft facility that a rural household is entitled to. And it’s the only credit facility that is repaid through manual work provided by the banker. Neat.

And it has a livelihoods value, in Karnataka, of Rs 28,900. 100 days of work x Rs 289.

For People with Disabilities, the entitlement is 150 days, and that is separate from the 100 days their family is already entitled to. That’s Rs 72,250 per annum.

Governments hate it, apart from election time, because it places a burden on the exchequer. But for a household surviving on its ability to do manual work, it eases their burden of surviving for 100 days of the year.

Adaptation

Adaptation

MGNREGA was designed as food security. But its intrinsic design and focus on rural areas makes it a climate adaptation resource. And its eligibility criteria – SC/ST households, small & marginal farmers, PWDs … – makes it a social targeting dream.

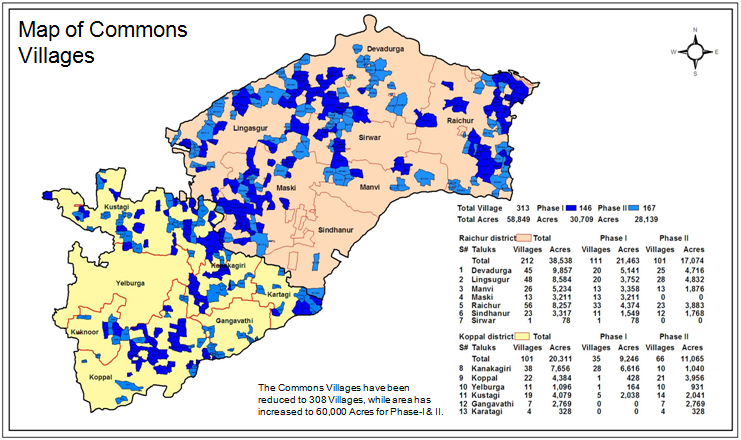

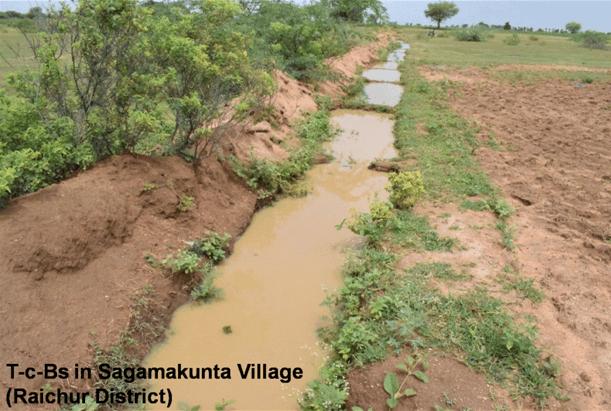

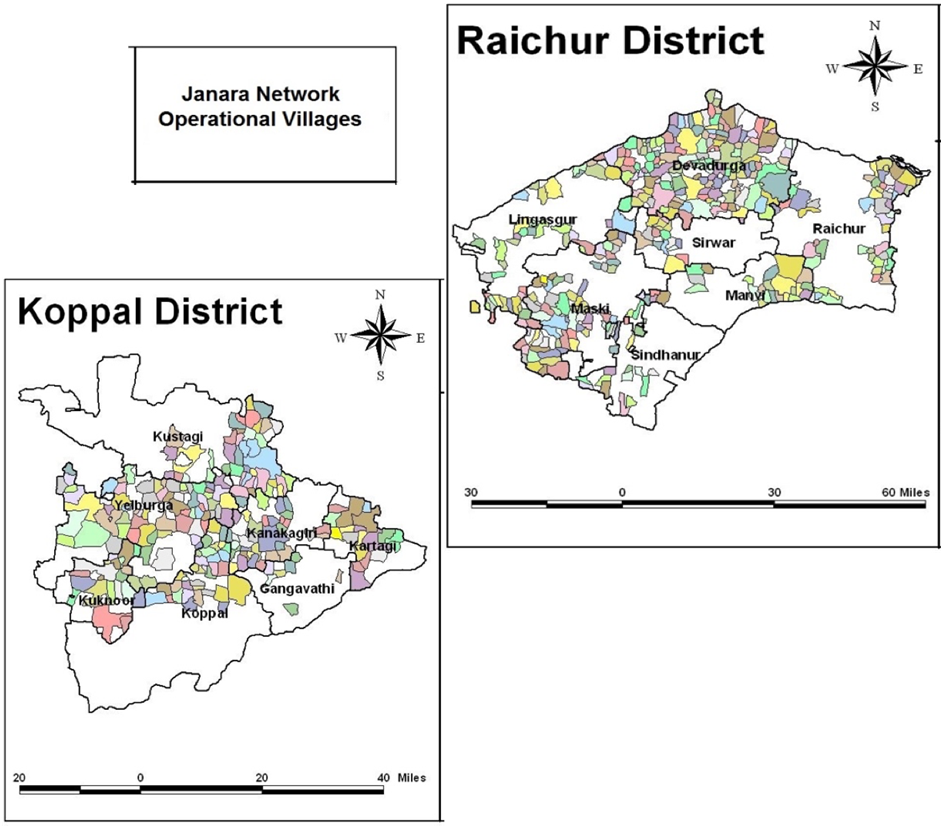

For climate-vulnerable communities in Raichur and Koppal districts, MGNREGA is also being used to treat and develop Commons in 308 villages.

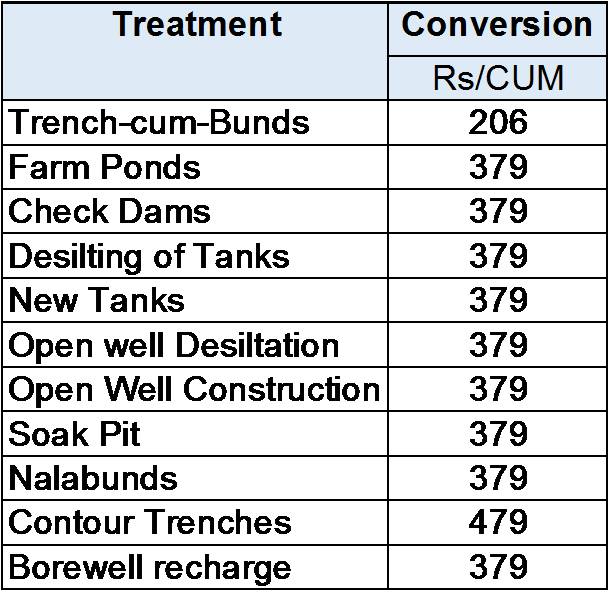

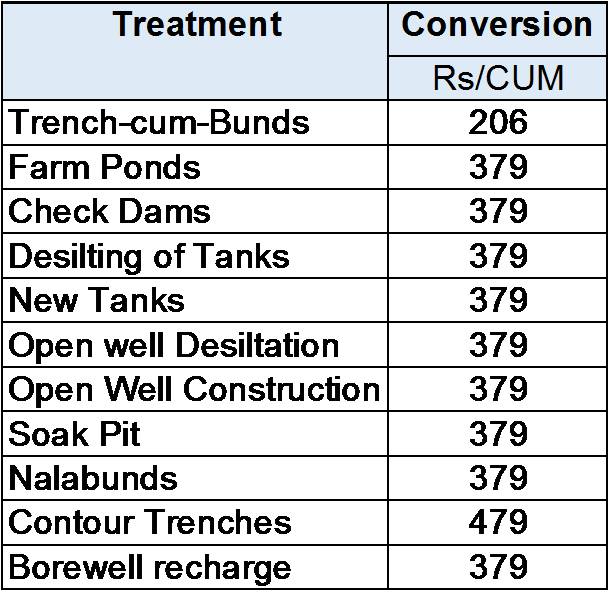

MGNREGA Treatments contributing to Water Holding Capacity

And for Small & Marginal farmers, the adaptation resources are a windfall: Rs 10,956 for Trench-cum-Bunds per acre, Rs 50-80,000 for Farm ponds, Rs 2-10 Lakhs for Check dams and Rs 2-5 Lakhs for Nala bunds.

Presently, 5,763 farmers have accessed MGNREGA resources for their lands.

Janara Network is now exploring how these farmers can explore dryland horticulture on these lands, also with MGNREGA resources.

And we’d like to explore aeroponics and assured irrigation through harvesting rainwater on 1 ac plots in the near future.

Water

Water-stressed and Climate-vulnerable: Raichur and Koppal districts form a mix of the best and the worst: these have canal irrigation from the Tungabhadra Canals as well as from the Upper Krishna Project. Yet, Devadurga taluk, which before canal-irrigation was amongst the 100 most backward taluks in the country where MGNREGA was rolled out first, still has 10 Gram Panchayats which continue to be dry villages.

Of the 1514 villages in the two districts, 981 (65%) are dry, 223 (15%) have both wet and dry lands, while 310 (20%) are wet villages.

Rural communities, which were once categorised as Dry, Wet and Both, are now finding that all water for irrigation, from canals, lift irrigation projects or groundwater,is ultimately dependent on rain for recharge. A funny way would be to describe all rural households as being in the same boat, and being left high and dry….

Water Holding Capacity in the Drylands. Janara Network has successfully used MGNREGA resources to build 27,25,704 CUM of Water Holding Capacity in 280 villages of Raichur and Koppal districts, through MGNREGA Resources.

This Water holding capacity allows for 10.90 Billion litres rainwater to be conservatively harvested every year, assuming just 4x16mm Rain Events per annum.

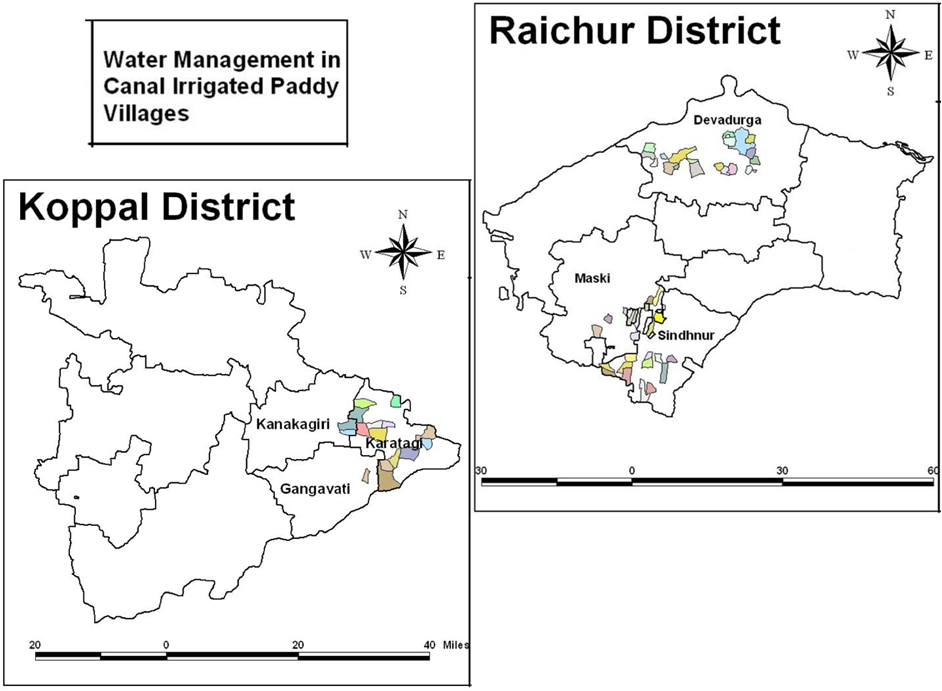

Water savings in canal-irrigated paddy cultivation. Koppal is irrigated by the Tungabhadra Left Bank Canal (TLBC), while Raichur is irrigated by both the TLBC and the Upper Krishna Project. Janara Network works with paddy farmers in 82 villages of these two districts. its cultivation practices help farmers to save 2 million litres of canal water per ac (as an avg of 8 yrs).

It’s two interventions with these farmers focus on

- Water Management + Line Planting as a LoWater cultivation practice and as a climate adaptation intervention that reduces dependency on water, reduces the cost of pest management, even as it contributes to an 8% increase in yield; and

- Canal-irrigated NPM (Non-Pesticide Management) paddy cultivation as an adaptation and sustainable agriculture intervention. This provides an average savings of Rs 3,405 per ac in savings from not using synthetic pesticides, apart from growing rice that is safe and contributes to a health soil and environment, healthier working conditions for farmers and labourers, as well healthier produce for consumers;

These two interventions have saved 331.34 B/L canal water since 2014.

NPM

(Non-Pesticide Management)

Paddy

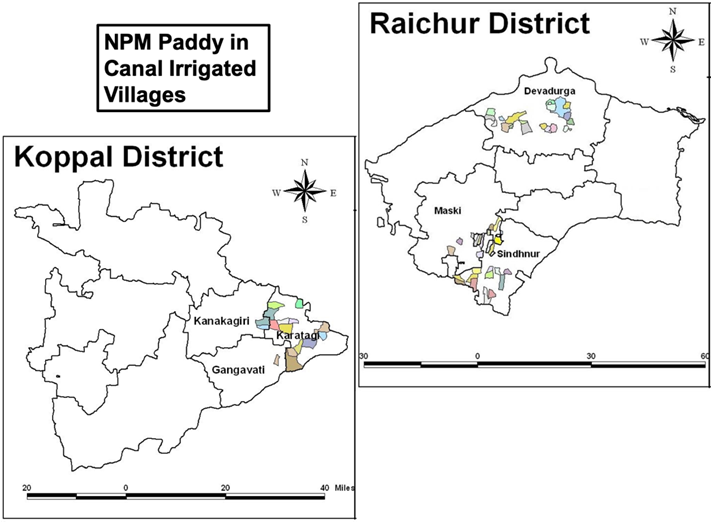

Through JSMBT, Janara Network’s NPM paddy farmers are members of the NPM Initiative, a network of NPM farmers across the different regions of India.

NPM Rice milled from this paddy is sold through Safe Harvest as a ‘0’ Pesticide product.

NPM Paddy results in an average savings of Rs 3,405 per ac from not using synthetic pesticides.

Added benefits include a safer farming experience, growing rice that is safe and contributes to a health soil and environment, healthier working conditions for farmers and labourers, as well healthier produce for consumers;

While Devadurga is the focal point for our NPM paddy intervention, inroads are slowly being made in the Tunga villages also. The scenario here is bleak.

Karatagi and Sindhanur, under TLBC command area are known for intensive farming with high external inputs due to canal irrigation for the last 50 years. Farmers cultivate paddy during Kharif and Rabi seasons. This region is one of the highest pesticide contamination regions in the country. This is compounded by high level usage of water, which in turn promotes a fertile environment for pests.

Fertilizer and synthetic pesticide sales people have marketed the fear of crop failure amongst farmers. This is best certified by the presence of 27 shops selling these in a single street in Siddapura Gram Panchayat in Gangavati taluk.

Indiscriminateuse of pesticides in the region has made this an endemic zone for Brown Plant Hoppers (BPH). Farmers spend about Rs 7000 to 10,000 per acre to manage this single pest during the Kharif paddy.,

The use of excess fertilizer and synthetic pesticides has systematically poisoned the lands and, often the farmers and labourers themselves handling these, leading to crisis in environment. It has been reported that traces of these pesticides have led to rice from this region being rejected in international markets. And there are reports of cattle being fed on fresh paddy straw in the region, and dying. Unfortunately, farmer beliefs and practices have multiple economic impacts. The key being that paddy is seen as the best cash crop, though there are many other crops which do financially better when gross income is converted into net income.

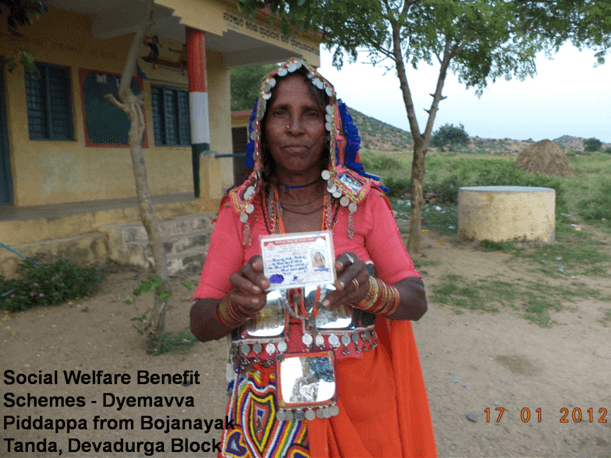

Public Resources

Social Welfare Benefits and Entitlements provide a safety net that allow poor and vulnerable households to lead lives with a little more dignity.

MGNREGA provides a rural household with a committed cashflow of Rs 28,900 per year.

Similarly, the 5% reservation for PWDs in all Gram Panchayat budget lines provides a varied menu of options to PWD households to allow them to match public resources to needs in the most relevant way.

Janara Network is committed to facilitate 100% access to eligible households and individuals to available SWBs and Entitlements.

Integrated Village Development

Does one look at needs in isolation or as a whole?

Can one’s responses be modular so that new needs can be added without disturbing frameworks and processes already in place?

Janara Network has identified 1 Gram Panchayat each in Raichur and Koppal district to see how its existing interventions can be integrated into a single village: micro credit, work security, adaptation, public resources, with either or both dryland and paddy farming.

This will be reported in detail as we establish the first of the IVD villages.